You Have One Job – Lessons from a Competitive CrossFit Coach

You Have One Job – Lessons from a Competitive CrossFit Coach

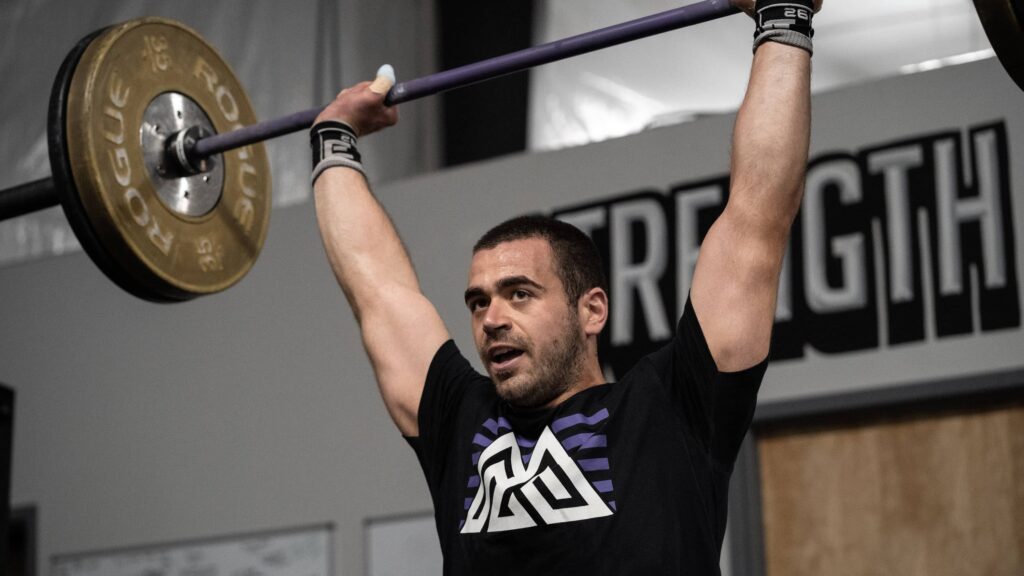

While 2021 isn’t over yet, we are rapidly approaching the competitive CrossFit season. In Maine, the bay doors have closed, daylight is now subordinate to darkness, and looming landmarks like Wodapalooza, competition block programming, Quarterfinals, and the start of the competitive season accelerate to the forefront of the Misfit Athletics operational battle rhythm. As coaches, athletes are now more attuned to the urgency of online qualifiers and significant pre-season events, which means we are too. For Misfit Athletics, 2021 brought plenty of ups and downs, and failing to learn and reflect from wins and losses would create a doomed-to-repeat scenario. We spend plenty of time internally reflecting on things we’ve observed and mistakes we’ve made, so today, I’m going to share my reflection process and some of the lessons I’ve learned throughout the 2021 season. For those with limited experience and exposure to mentors, I can give you a glimpse of what’s necessary if you want to be a coach worth your salt in the competitive space. Coaches need to have the range to operate both on the ground floor and in the control tower with the 10,000-foot view; it’s knowing what to do in between is where you make your money. At the end of the day, nothing I say is relevant unless you can apply it in the only way that matters: helping your athletes realize their full potential.

We’ll get started with some concrete facts that will lay the groundwork for success throughout the weekend. Still, it’s important to remember that while things like filling water bottles are instantaneously helpful, your job is far more about providing the stability that is difficult for an athlete to maintain regardless of how the weekend progresses. Remember that athletes are experiencing a degree of sensory overload that is difficult to replicate and that they are not only expecting themselves to adapt but to thrive in a completely new environment. Your job is to facilitate that success to the best of your ability.

Little Things are Big Things

No one could argue that CrossFit athletes don’t know how to put their nose to the grindstone when it comes to training or crank the intensity up to eleven when it’s time to compete. For most athletes, the volume of competition is lower than a typical training day, but the intensity is ratcheted way up.

Thanks, coach; tell us something we don’t already know.

Many athletes and coaches forget about the added demands of simple things like coral times, event briefings, walking from location to location within the venue, and all of the associated stress and fatigue that accompanies these things. At events like Granite Games and the CrossFit Games, athletes walk multiple miles per day just solely to get from point a to point b or from the corral to their starting mats. At the Games specifically, athletes are often sequestered for multiple hours at a time, unable to leave (the Colosseum basement, for example) to get food or rest in a comfortable location. Conversely, when training at their home gyms, athletes are essentially only moving during training and have all of their creature comforts within reach. Their cars are parked nearby, their workouts are all performed in the same building, and there is minimal “non-exercise stress” associated with training (not to mention they can sleep in their own beds). When these conveniences are turned into stressors, they contribute to both the athlete and coach’s mental and physical exhaustion. It’s imperative that we are taking stock and are reminding athletes to do things to combat these issues like packing additional food, water, electrolytes, recovery tools, etc.. You cannot count on these things being readily available and will drain athletes of their energy just as quickly as an event will. (A quick side note – this applies equally to coaches. Take care of yourself so you can take care of your athlete – it does nothing to play the hero who isn’t fueling themselves to appear invincible.) With summer competitions, heat can play a massive role that many athletes are unprepared for, and suppressing the effects of the elements is a big part of our job so that athletes can focus on execution. The bottom line is that competition adds an entirely different layer to how athletes will perform, and we need to do our best to mitigate as many of these stressors as possible.

Once the little things are taken care of, our jobs rapidly become some collaboration of coach and therapist in constantly changing proportions. Your athlete has put the work in, and your job goes from refining pull-up technique to a much more cerebral competition sherpa. We now need to create an environment that extracts the maximum potential from the athlete while remembering that they want as badly as you do to succeed. A firm yet supportive mentor is a good starting point, with the range to flex in either direction as the weekend unfolds.

Be a Thermostat, Not a Thermometer

Throughout the weekend, things will both go as planned and come off the tracks in a matter of seconds. The higher the expectations, the greater the emotional swings both you and your athlete will experience. The difference is, your athlete is the thermometer, and you need to be the thermostat. You control the temperature in the room by not becoming a celebratory five-year-old when things go your way or a psychotic degenerate ready to blame everyone else when things go wrong. It’s necessary to be excited for your athlete in the same way it’s necessary to console them if things don’t go to plan, but no single event tells the story of the weekend. Things will go wrong, a judge will unfairly alter the trajectory of an event, and athletes will respond instinctively in the moment without considering the downstream effects. The ebb and flow of competition is demanding both mentally and physically, and energy spent being overly emotional in either direction should be saved for the next event. As a coach, we keep the temperature in the room at a constant, allowing athletes to express their emotions without allowing it to overtake their headspace. Allow athletes time to process things when they go wrong, but be the one to bring homeostasis back to the athlete’s psyche.

Distractions and Reminders

Similarly, you must understand that not all athletes are the same person in training as they are in competition. The happy-go-lucky athlete in the gym who you’re concerned about not taking the competition seriously enough could be the athlete who needs almost no reminders to warm up properly and will mentally dial themselves in on their own. Conversely, the athlete who runs through a brick wall in training may need to be distracted from things like the leaderboard and require the most emotional support in competition. We’ve had athletes who need nothing more than a reminder of what time their heat is, and we’ve had athletes who need to be reminded that they’re fit despite being at the CrossFit Games (yes, really). There are endless permutations of the scenarios I’ve described, so you have to know which one your athlete is so that you can guide them accordingly. Ideally, you’ve developed a deep enough relationship with your athlete well ahead of time to know which camp they fall into, but every coach-athlete pair has their first event together. Whether it’s a soft reminder that they deserve to be there, a 1984 Herb Brooks motivational speech, or a shoulder to cry on when things go south, it’s our job to know which tool to apply to which situation.

Watch and Learn, But Sometimes Don’t

If you ever have the privilege to be in the athlete area with some of the fittest humans on earth and their coaches, you’d be missing a massive opportunity if you didn’t at least occasionally look around and observe what other coaches are doing (or not doing) to help their athletes. You have a golden opportunity to see things that you could add to your coaching toolkit and just as often watch things that make you wonder how the hell someone managed to procure a coach wristband. Understand that not all coaches are coaches and that part of that observational process is knowing what not to do, how not to treat your (or another) athlete, and what rules to follow (or occasionally choose not to). If you think you’re the smartest person in the room, that’s the fastest way to verify that you are not, in fact, the smartest person in the room. Assume you have something to learn from everyone, and capitalize on it.

You Have One Job

Maybe the biggest eye-opener for me happened during a conversation I had with Drew during the opening days of the Granite Games. As we stood in the athlete warm-up area, dozens of male and female athletes nervously jousted for platforms to warm up their snatch. At the same time, a comparatively similar number of coaches leaned over the barriers to provide coaching to their athletes.

“Most of these coaches will be gone by day 3,” Drew said. “It’ll be a ghost town on Sunday.”

What sounded somewhat ludicrous to me at the time came to fruition as athletes organized themselves on the leaderboard throughout the weekend. As the likelihood of Games qualification, a top 10 finish, a top-half finish, or whatever goal athletes had on day 1 diminished, so did the coaching staff. A staggeringly low number of coaches could be found rallying their athletes in the same way they were on day 1 when everyone was fully locked and loaded. The capitalist in me said, “good, maybe some of these athletes will see that the Misfit coaches are still dialed in,” while the former athlete and empathic coach in me couldn’t help but feel for the athletes. A year of hard work, and your coach couldn’t rally for three days? A year of training, and neither of you developed the relationship meaningful enough to cultivate a resiliency and fire to at least cross the finish line together? I fully understand the frustrations when things don’t go as planned, but your job as a coach isn’t refining snatch technique on game day – it’s building the scaffolding your athlete needs to reach beyond their limits for an event, whether it’s one day or five. The same consistency an athlete demonstrated throughout the year in training has to be matched by the coach, and if those things don’t happen, you both should do some self-reflection and ask, “where did I go wrong?” The athlete deserves to have you in their corner at maximum capacity for 100% of the weekend, and frankly, you deserve to pour your efforts into your role regardless of how the leaderboard shakes out.

In the same way CrossFit athletes need to be competent in a myriad of skills; you need to be competent in the things they aren’t. The coach-athlete bond is somewhere between a marriage and a therapist-patient relationship. When both parties understand and respect each other enough to know the other has their best interest in mind, the sky’s the limit. Given all of these lessons from a competition scenario, I’d be remiss if I didn’t remind you that the success of you and your athlete is predicated on a level of trust and mutual respect that is cultivated long before you put on your coach’s wristband. You can have all the technical knowledge and experience in the world, but none of it matters if an athlete doesn’t trust or respect you enough to adhere to the things you have to say. If you can foster that relationship and remember that your job is to extract the best from your athlete in a way that makes them proud to compete, you’re in.

Written by Hunter Wood